![]()

White House philosophy stoked mortgage bonfire

By Jo Becker, Sheryl Gay Stolberg and Stephen Labaton

Sunday, December 21, 2008

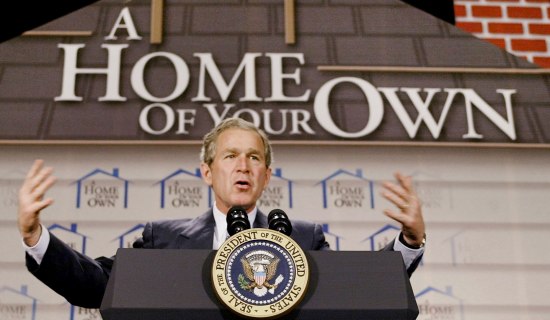

WASHINGTON : “We can put light where there’s darkness, and hope where there’s despondency in this country. And part of it is working together as a nation to encourage folks to own their own home.” President George W. Bush, Oct. 15, 2002

It was Sept. 18. Lehman Brothers had just gone belly-up, overwhelmed by toxic mortgages. Bank of America had swallowed Merrill Lynch in a hastily arranged sale. Two days earlier, Bush had agreed to pump $85 billion into the failing insurance giant American International Group.

The president listened as Ben Bernanke, chairman of the Federal Reserve, laid out the latest terrifying news: The credit markets, gripped by panic, had frozen overnight, and banks were refusing to lend money.

Then his Treasury secretary, Henry Paulson Jr., told him that to stave off disaster, he would have to sign off on the biggest government bailout in history.

Bush, according to several people in the room, paused for a single, stunned moment to take it all in.

“How,” he wondered aloud, “did we get here?”

Eight years after arriving in Washington vowing to spread the dream of homeownership, Bush is leaving office, as he himself said recently, “faced with the prospect of a global meltdown” with roots in the housing sector he so ardently championed.

There are plenty of culprits, like lenders who peddled easy credit, consumers who took on mortgages they could not afford and Wall Street chieftains who loaded up on mortgage-backed securities without regard to the risk.

But the story of how we got here is partly one of Bush’s own making, according to a review of his tenure that included interviews with dozens of current and former administration officials.

From his earliest days in office, Bush paired his belief that Americans do best when they own their own home with his conviction that markets do best when let alone.

He pushed hard to expand homeownership, especially among minorities, an initiative that dovetailed with his ambition to expand the Republican tent and with the business interests of some of his biggest donors. But his housing policies and hands-off approach to regulation encouraged lax lending standards.

Bush did foresee the danger posed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored mortgage finance giants. The president spent years pushing a recalcitrant Congress to toughen regulation of the companies, but was unwilling to compromise when his former Treasury secretary wanted to cut a deal. And the regulator Bush chose to oversee them an old prep school buddy pronounced the companies sound even as they headed toward insolvency.

As early as 2006, top advisers to Bush dismissed warnings from people inside and outside the White House that housing prices were inflated and that a foreclosure crisis was looming. And when the economy deteriorated, Bush and his team misdiagnosed the reasons and scope of the downturn; as recently as February, for example, Bush was still calling it a “rough patch.”

The result was a series of piecemeal policy prescriptions that lagged behind the escalating crisis.

“There is no question we did not recognize the severity of the problems,” said Al Hubbard, Bush’s former chief economics adviser, who left the White House in December 2007. “Had we, we would have attacked them.”

Looking back, Keith Hennessey, Bush’s current chief economics adviser, says he and his colleagues did the best they could “with the information we had at the time.” But Hennessey did say he regretted that the administration did not pay more heed to the dangers of easy lending practices. And both Paulson and his predecessor, John Snow, say the housing push went too far.

“The Bush administration took a lot of pride that homeownership had reached historic highs,” Snow said in an interview. “But what we forgot in the process was that it has to be done in the context of people being able to afford their house. We now realize there was a high cost.”

For much of the Bush presidency, the White House was preoccupied by terrorism and war; on the economic front, its pressing concerns were cutting taxes and privatizing Social Security. The housing market was a bright spot: ever-rising home values kept the economy humming, as owners drew down on their equity to buy consumer goods and pack their children off to college.

Lawrence Lindsay, Bush’s first chief economics adviser, said there was little impetus to raise alarms about the proliferation of easy credit that was helping Bush meet housing goals.

“No one wanted to stop that bubble,” Lindsay said. “It would have conflicted with the president’s own policies.”

Today, millions of Americans are facing foreclosure, homeownership rates are virtually no higher than when Bush took office, Fannie and Freddie are in a government conservatorship, and the bailout cost to taxpayers could run in the trillions.

As the economy has shed jobs 533,000 last month alone and his party has been punished by irate voters, the weakened president has granted his Treasury secretary extraordinary leeway in managing the crisis.

Never once, Paulson said in a recent interview, has Bush overruled him. “I’ve got a boss,” he explained, who “understands that when you’re dealing with something as unprecedented and fast-moving as this we need to have a different operating style.”

Paulson and other senior advisers to Bush say the administration has responded well to the turmoil, demonstrating flexibility under difficult circumstances. “There is not any playbook,” Paulson said.

The president declined to be interviewed for this article. But in recent weeks Bush has shared his views of how the nation came to the brink of economic disaster. He cites corporate greed and market excesses fueled by a flood of foreign cash “Wall Street got drunk,” he has said and the policies of past administrations. He blames Congress for failing to reform Fannie and Freddie. Last week, Fox News asked Bush if he was worried about being the Herbert Hoover of the 21st century.

“No,” Bush replied. “I will be known as somebody who saw a problem and put the chips on the table to prevent the economy from collapsing.”

But in private moments, aides say, the president is looking inward. During a recent ride aboard Marine One, the presidential helicopter, Bush sounded a reflective note.

“We absolutely wanted to increase homeownership,” Tony Fratto, his deputy press secretary, recalled him saying. “But we never wanted lenders to make bad decisions.”

A policy gone awry

Darrin West could not believe it. The president of the United States was standing in his living room.

It was June 17, 2002, a day West recalls as “the highlight of my life.” Bush, in Atlanta to unveil a plan to increase the number of minority homeowners by 5.5 million, was touring Park Place South, a development of starter homes in a neighborhood once marked by blight and crime.

West had patrolled there as a police officer, and now he was the proud owner of a $130,000 town house, bought with an adjustable-rate mortgage and a $20,000 government loan as his down payment just the sort of creative public-private financing Bush was promoting.

“Part of economic security,” Bush declared that day, “is owning your own home.”

A lot has changed since then. West, beset by personal problems, left Atlanta. Unable to sell his home for what he owed, he said, he gave it back to the bank last year. Like other communities across America, Park Place South has been hit with a foreclosure crisis affecting at least 10 percent of its 232 homes, according to Masharn Wilson, a developer who led Bush’s tour.

“I just don’t think what he envisioned was actually carried out,” she said.

Park Place South is, in microcosm, the story of a well-intentioned policy gone awry. Advocating homeownership is hardly novel; the Clinton administration did it, too. For Bush, it was part of his vision of an “ownership society,” in which Americans would rely less on the government for health care, retirement and shelter. It was also good politics, a way to court black and Hispanic voters.

But for much of Bush’s tenure, government statistics show, incomes for most families remained relatively stagnant while housing prices skyrocketed. That put homeownership increasingly out of reach for first-time buyers like West.

So Bush had to, in his words, “use the mighty muscle of the federal government” to meet his goal. He proposed affordable housing tax incentives. He insisted that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac meet ambitious new goals for low-income lending.

Concerned that down payments were a barrier, Bush persuaded Congress to spend up to $200 million a year to help first-time buyers with down payments and closing costs.

And he pushed to allow first-time buyers to qualify for federally insured mortgages with no money down. Republican congressional leaders and some housing advocates balked, arguing that homeowners with no stake in their investments would be more prone to walk away, as West did. Many economic experts, including some in the White House, now share that view.

The president also leaned on mortgage brokers and lenders to devise their own innovations. “Corporate America,” he said, “has a responsibility to work to make America a compassionate place.”

And corporate America, eyeing a lucrative market, delivered in ways Bush might not have expected, with a proliferation of too-good-to-be-true teaser rates and interest-only loans that were sold to investors in a loosely regulated environment.

“This administration made decisions that allowed the free market to operate as a barroom brawl instead of a prize fight,” said L. William Seidman, who advised Republican presidents and led the savings and loan bailout in the 1990s. “To make the market work well, you have to have a lot of rules.”

But Bush populated the financial system’s alphabet soup of oversight agencies with people who, like him, wanted fewer rules, not more.

Like minds on laissez-faire

The president’s first chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission promised a “kinder, gentler” agency. The second was pushed out amid industry complaints that he was too aggressive. Under its current leader, the agency failed to police the catastrophic decisions that toppled the investment bank Bear Stearns and contributed to the current crisis, according to a recent inspector general’s report.

As for Bush’s banking regulators, they once brandished a chain saw over a 9,000-page pile of regulations as they promised to ease burdens on the industry. When states tried to use consumer protection laws to crack down on predatory lending, the comptroller of the currency blocked the effort, asserting that states had no authority over national banks.

The administration won that fight at the Supreme Court. But Roy Cooper, North Carolina’s attorney general, said, “They took 50 sheriffs off the beat at a time when lending was becoming the Wild West.”

The president did push rules aimed at forcing lenders to more clearly explain loan terms. But the White House shelved them in 2004, after industry-friendly members of Congress threatened to block confirmation of his new housing secretary.

In the 2004 election cycle, mortgage bankers and brokers poured nearly $847,000 into Bush’s re-election campaign, more than triple their contributions in 2000, according to the nonpartisan Center for Responsive Politics. The administration did not finalize the new rules until last month.

Among the Republican Party’s top 10 donors in 2004 was Roland Arnall. He founded Ameriquest, then the nation’s largest lender in the subprime market, which focuses on less creditworthy borrowers. In July 2005, the company agreed to set aside $325 million to settle allegations in 30 states that it had preyed on borrowers with hidden fees and ballooning payments. It was an early signal that deceptive lending practices, which would later set off a wave of foreclosures, were widespread.

Andrew Card Jr., Bush’s former chief of staff, said White House aides discussed Ameriquest’s troubles, though not what they might portend for the economy. Bush had just nominated Arnall as his ambassador to the Netherlands, and the White House was primarily concerned with making sure he would be confirmed.

“Maybe I was asleep at the switch,” Card said in an interview.

Brian Montgomery, the Federal Housing Administration commissioner, understood the significance. His agency insures home loans, traditionally for the same low-income minority borrowers Bush wanted to help. When he arrived in June 2005, he was shocked to find those customers had been lured away by the “fool’s gold” of subprime loans. The Ameriquest settlement, he said, reinforced his concern that the industry was exploiting borrowers.

In December 2005, Montgomery drafted a memo and brought it to the White House. “I don’t think this is what the president had in mind here,” he recalled telling Ryan Streeter, then the president’s chief housing policy analyst.

It was an opportunity to address the risky subprime lending practices head on. But that was never seriously discussed. More senior aides, like Karl Rove, Bush’s chief political strategist, were wary of overly regulating an industry that, Rove said in an interview, provided “a valuable service to people who could not otherwise get credit.” While he had some concerns about the industry’s practices, he said, “it did provide an opportunity for people, a lot of whom are still in their houses today.”

The White House pursued a narrower plan offered by Montgomery that would have allowed the FHA to loosen standards so it could lure back subprime borrowers by insuring similar, but safer, loans. It passed the House but died in the Senate, where Republican senators feared that the agency would merely be mimicking the private sector’s risky practices a view Rove said he shared.

Looking back at the episode, Montgomery broke down in tears. While he acknowledged that the bill did not get to the root of the problem, he said he would “go to my grave believing” that at least some homeowners might have been spared foreclosure.

Today, administration officials say it is fair to ask whether Bush’s ownership push backfired. Paulson said the administration, like others before it, “over-incented housing.” Hennessey put it this way: “I would not say too much emphasis on expanding homeownership. I would say not enough early focus on easy lending practices.”

‘We told you so’

Armando Falcon Jr. was preparing to take on a couple of giants.

A soft-spoken Texan, Falcon ran the Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, a tiny government agency that oversaw Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two pillars of the American housing industry. In February 2003, he was finishing a blockbuster report that warned the pillars could crumble.

Created by Congress, Fannie and Freddie called GSE’s, for government-sponsored entities bought trillions of dollars’ worth of mortgages to hold or sell to investors as guaranteed securities. The companies were also Washington powerhouses, stuffing lawmakers’ campaign coffers and hiring bare-knuckled lobbyists.

Falcon’s report outlined a worst-case situation in which Fannie and Freddie could default on debt, setting off “contagious illiquidity in the market” in other words, a financial meltdown. He also raised red flags about the companies’ soaring use of derivatives, the complex financial instruments that economic experts now blame for spreading the housing collapse.

Today, the White House cites that report and its subsequent effort to better regulate Fannie and Freddie as evidence that it foresaw the crisis and tried to avert it. Bush officials recently wrote up a talking points memo headlined “GSE’s We Told You So.”

But the back story is more complicated. To begin with, on the day Falcon issued his report, the White House tried to fire him.

At the time, Fannie and Freddie were allies in the president’s quest to drive up homeownership rates; Franklin Raines, then Fannie’s chief executive, has fond memories of visiting Bush in the Oval Office and flying aboard Air Force One to a housing event. “They loved us,” he said.

So when Falcon refused to deep-six his report, Raines took his complaints to top Treasury officials and the White House. “I’m going to do what I need to do to defend my company and my position,” Raines told Falcon.

Days later, as Falcon was in New York preparing to deliver a speech about his findings, his cellphone rang. It was the White House personnel office, he said, telling him he was about to be unemployed.

His warnings were buried in the next day’s news coverage, trumped by the White House announcement that Bush would replace Falcon, a Democrat appointed by Bill Clinton, with Mark Brickell, a leader in the derivatives industry that Falcon’s report had flagged.

It was not until 2003, when Freddie became embroiled in an accounting scandal, that the White House took on the companies in earnest. Bush decided to quit the long-standing practice of rewarding supporters with high-paying appointments to the companies’ boards “political plums,” in Rove’s words. He also withdrew Brickell’s nomination and threw his support behind Falcon, beginning an intense effort to give his little regulatory agency more power.

Falcon lacked explicit authority to limit the size of the companies’ mammoth investment portfolios, or tell them how much capital they needed to guard against losses. White House officials wanted that to change. They also wanted the power to put the companies into receivership, hoping that would end what Card, the former chief of staff, called “the myth of government backing,” which gave the companies a competitive edge because investors assumed the government would not let them fail.

By the spring of 2005 a deal with Congress seemed within reach, Snow, the former Treasury secretary, said in an interview.

Michael Oxley, an Ohio Republican and then-chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, had produced what Snow viewed as “a pretty darned good bill,” a watered-down version of what the president sought. But at the urging of Card and the White House economics team, the president decided to hold out for a tougher bill in the Senate.

Card said he feared that Snow was “more interested in the deal than the result.” When the bill passed the House, the president issued a statement opposing it, effectively killing any chance of compromise. Oxley was furious.

“The problem with those guys at the White House, they had all the answers and they didn’t think they had to listen to anyone, including the Treasury secretary,” Oxley said in a recent interview. “They were driving the ideological train. He was in the caboose, and they were in the engine room.”

Card and Hennessey said they had no regrets. They are convinced, Hennessey said, that the Oxley bill would have produced “the worst of all possible outcomes,” the illusion of reform without the substance.

Still, some former White House and Treasury officials continue to debate whether Bush’s all-or-nothing approach scuttled a measure that, while imperfect, might have given an aggressive regulator enough power to keep the companies from failing.

Snow, for one, calls Oxley “a hero,” adding, “He saw the need to move. It didn’t get done. And it’s too bad, because I think if it had, I think we could well have avoided a big contributor to the current crisis.”

Unheeded warnings

Jason Thomas had a nagging feeling.

The New Century Financial Corp., a huge subprime lender whose mortgages were bundled into securities sold around the world, was headed for bankruptcy in March 2007. Thomas, an economic analyst for Bush, was responsible for determining whether it was a hint of things to come.

At 29, Thomas had followed a fast-track career path that took him from a Buffalo meatpacking plant, where he worked as a statistician, to the White House. He was seen as a whiz kid, “a brilliant guy,” his former boss, Hubbard, says.

As Thomas began digging into New Century’s failure that spring, he became fixated on a particular statistic, the rent-to-own ratio.

Typically, as home prices increase, rental costs rise proportionally. But Thomas sent charts to top White House and Treasury officials showing that the monthly cost of owning far outpaced the cost to rent. To Thomas, it was a sign that housing prices were wildly inflated and bound to plunge, a condition that could set off a foreclosure crisis as conventional and subprime borrowers with little equity found they owed more than their houses were worth.

It was not the Bush team’s first warning. The previous year, Lindsay, the former chief economics adviser, returned to the White House to tell his old colleagues that housing prices were headed for a crash. But housing values are hard to evaluate, and Lindsay had a reputation as a market pessimist, said Hubbard, adding, “I thought, ‘He’s always a bear.’ “

In retrospect, Hubbard said, Lindsay was “absolutely right,” and Thomas’s charts “should have been a signal.”

Instead, the prevailing view at the White House was that the problems in the housing market were limited to subprime borrowers unable to make their payments as their adjustable mortgages reset to higher rates. That belief was shared by Bush’s new Treasury secretary, Paulson.

Paulson, a former chairman of the Wall Street firm Goldman Sachs, had been given unusual power; he had accepted the job only after the president guaranteed him that Treasury, not the White House, would have the dominant role in shaping economic policy. That shift merely continued an imbalance of power that stifled robust policy debate, several former Bush aides say.

Throughout the spring of 2007, Paulson declared that “the housing market is at or near the bottom,” with the problem “largely contained.” That position underscored nearly every action the Bush administration took in the ensuing months as it offered one limited response after another.

By that August, the problems had spread beyond New Century. Credit was tightening, amid questions about how heavily banks were invested in securities linked to mortgages. Still, Bush predicted that the turmoil would resolve itself with a “soft landing.”

The plan Bush announced on Aug. 31 reflected that belief. Called “FHA Secure,” it aimed to help about 80,000 homeowners refinance their loans. Montgomery, the housing commissioner, said that he knew the modest program was not enough the White House later expanded the agency’s rescue role and that he would be “flying the plane and fixing it at the same time.”

That fall, Representative Rahm Emanuel, a leading Democrat, former investment banker and now the incoming chief of staff to President-elect Barack Obama, warned the White House it was not doing enough. He said he told Joshua Bolten, Bush’s chief of staff, and Paulson in a series of phone calls that the credit crisis would get “deep and serious” and that the only answer was big, internationally coordinated government intervention.

“You got to strangle this thing and suffocate it,” he recalled saying.

Instead, Bush developed Hope Now, a voluntary public-private partnership to help struggling homeowners refinance loans. And he worked with Congress to pass a stimulus package that sent taxpayers $150 billion in tax rebates.

In a speech to the Economic Club of New York in March 2008, he cautioned against Washington’s temptation “to say that anything short of a massive government intervention in the housing market amounts to inaction,” adding that government action could make it harder for the markets to recover.

Dominoes Start to Fall

Within days, Bear Sterns collapsed, prompting the Federal Reserve to engineer a hasty sale. Some economic experts, including Timothy Geithner, the president of the New York Federal Reserve Bank (and Obama’s choice for Treasury secretary) feared that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could be the next to fall.

Bush was still leaning on Congress to revamp the tiny agency that oversaw the two companies, and had acceded to Paulson’s request for the negotiating room that he had denied Snow. Still, there was no deal.

Over the previous two years, the White House had effectively set the agency adrift. Falcon left in 2005 and was replaced by a temporary director, who was in turn replaced by James Lockhart, a friend of Bush from their days at Andover, and a former deputy commissioner of the Social Security Administration who had once run a software company.

In an Oval Office meeting on March 17, however, Paulson barely mentioned the idea, according to several people present. He wanted to use the troubled companies to unlock the frozen credit market by allowing Fannie and Freddie to buy more mortgage-backed securities from overburdened banks. To that end, Lockhart’s office planned to lift restraints on the companies’ huge portfolios a decision derided by former White House and Treasury officials who had worked so hard to limit them.

But Paulson told Bush the companies would shore themselves up later by raising more capital.

“Can they?” Bush asked.

“We’re hoping so,” the Treasury secretary replied.

That turned out to be incorrect, and did not surprise Thomas, the Bush economic adviser. Throughout that spring and summer, he warned the White House and Treasury that, in the stark words of one e-mail message, “Freddie Mac is in trouble.” And Lockhart, he charged, was allowing the company to cover up its insolvency with dubious accounting maneuvers.

But Lockhart continued to offer reassurances. In a July appearance on CNBC, he declared that the companies were well managed and “worsts were not coming to worst.” An infuriated Thomas sent a fresh round of e-mail messages accusing Lockhart of “pimping for the stock prices of the undercapitalized firms he regulates.”

Lockhart defended himself, insisting in an interview that he was aware of the companies’ vulnerabilities, but did not want to rattle markets.

“A regulator,” he said, “does not air dirty laundry in public.”

Soon afterward, the companies’ stocks lost half their value in a single day, prompting Congress to quickly give Paulson the power to spend $200 billion to prop them up and to finally pass Bush’s long-sought reform bill, but it was too late. In September, the government seized control of Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

In an interview, Paulson said the administration had no justification to take over the companies any sooner. But Falcon disagreed: “They absolutely could have if they had thought there was a real danger.”

By Sept. 18, when Bush and his team had their fateful meeting in the Roosevelt Room after the failure of Lehman Brothers and the emergency rescue of AIG, Paulson was warning of an economic calamity greater than the Great Depression. Suddenly, historic government intervention seemed the only option. When Paulson spelled out what would become a $700 billion plan to rescue the nation’s banking system, the president did not hesitate.

“Is that enough?” Bush asked.

“It’s a lot,” the Treasury secretary recalled replying. “It will make a difference.” And in any event, he told Bush, “I don’t think we can get more.”

As the meeting wrapped up, a handful of aides retreated to the White House Situation Room to call Vice President Dick Cheney in Florida, where he was attending a fund-raiser. Cheney had long played a leading role in economic policy, though housing was not a primary interest, and like Bush he had a deep aversion to government intervention in the market. Nonetheless, he backed the bailout, convinced that too many Americans would suffer if Washington did nothing.

Bush typically darts out of such meetings quickly. But this time, he lingered, patting people on the back and trying to soothe his downcast staff. “During times of adversity, he bucks everybody up,” Paulson said.

It was not the end of the failures or government interventions; the administration has since stepped in to rescue Citigroup and, just last week, the Detroit automakers. With 31 days left in office, Bush says he will leave it to historians to analyze “what went right and what went wrong,” as he put it in a speech last week to the American Enterprise Institute.

Bush said he was too focused on the present to do much looking back.

“It turns out,” he said, “this isn’t one of the presidencies where you ride off into the sunset, you know, kind of waving goodbye.”

The global financial system was teetering on the edge of collapse when President George W. Bush and his economics team huddled in the Roosevelt Room of the White House for a briefing that, in the words of one participant, “scared the hell out of everybody.”