Super Bowl

Bank of America Throws Ten Million Dollar Super Bowl Party

AIG, Bank of america, Banking, Bear Stearns, CDS, Citibank, Derivatives, Finance, Hedge Funds, Merrill, Sports Business

Just weeks ago, the federal government extended $20 billion to Bank of America to keep it afloat, bringing its total in federal bailout dollars received to $45 billion. ABC News reports, however, that the bank managed to scrounge up millions of dollars to be an NFL sponsor and for “a five day carnival-like” Super Bowl party just outside the stadium:

The event — known as the NFL Experience — was 850,000 square feet of sports games and interactive entertainment attractions for football fans and was blanketed in Bank of America logos and marketing calls to sign up for football-themed banking products. […]

The bank refused to tell ABC News how much it is spending as an NFL corporate sponsor, but insiders have put the figure at close to $10 million. The NFL Experience was on top of that and was inked last summer, according to the bank.

The NFL said it was a “multi-million dollar” event and that it was also spending money to put on the event. A Super Bowl insider said the tents alone cost over $800,000.

The Huffington Post notes that this is the latest in a series of bailed-out banks that continue to spend lavishly on sports sponsorships.

Hail To The Redskins at the Pro Football Hall Of Fame

Stories“Hail To The Redskins- Hail Victory….

Braves On The Warpath- Fight For Old D.C.!“

A Class Reunion in Canton

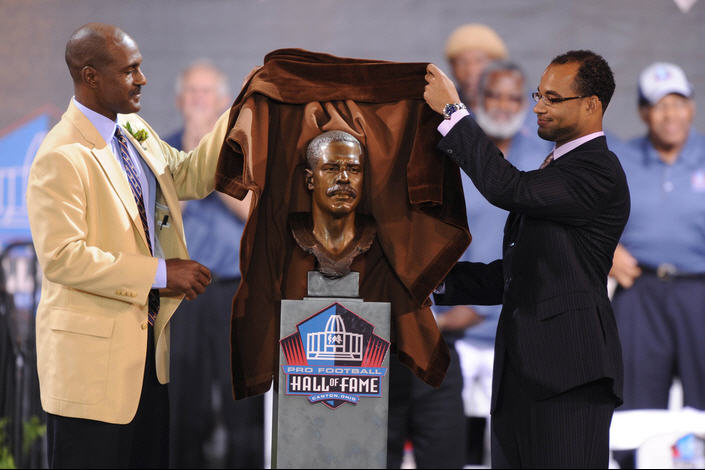

Partisan Crowd Cheers Monk, Green On Induction Day

By Mike Wise

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, August 3, 2008; D01

CANTON, Ohio, Aug. 2 — They came from the District and beyond to see them. Way beyond. Some of the pilgrimages began in Orange County, Calif., and others in Murphy, N.C., where a white-haired couple began driving through the Blue Ridge Mountains some nine hours earlier.

“After all the memories, we had to see them go in,” Bill Garrod said as his wife, Nancy, nodded in agreement, hours before Art Monk and Darrell Green were to be enshrined in the Pro Football Hall of Fame on Saturday.

And the moment the last Class of 2008 inductee took the stage, their patience was rewarded for those $4 gallons of gas and hours on sweltering freeways — just as Monk’s patience the past eight years was rewarded.

For 4 minutes 4 seconds before Monk spoke — an applause lasting nearly three times as long as that for any other honoree — the steadiest and most reliable wide receiver to play pro football in Washington took in the chants, smiles and unconditional love heaped upon him.

“Thank you, thank you,” Monk kept saying, happily unable to quiet the applause from the announced crowd of 16,654 at Fawcett Stadium, about 15,000 of whom wore burgundy and gold.

Green had spoken nearly an hour earlier, drawing a monstrous ovation as fireworks cascaded behind him. He was the third inductee to be honored and the first Redskin introduced.

Bill Garrod wore one of those Super Bowl T-shirts with the caricatured mugs of Redskins players from another era. There was Charles Mann, Earnest Byner, Ricky Sanders and, of course, the ebullient and grinning Green. Bill spoke of seeing Eddie LeBaron play at Griffith Stadium in the 1950s the way others spoke of the magic and majesty of RFK in the 1980s and early 1990s.

They overwhelmed this lush, northeastern Ohio town about an hour south of Cleveland with numbers and passion, thousands of fans clad in burgundy and gold hats, jerseys, assorted paraphernalia and, yes, Halloween masks. They dwarfed other Hall of Fame inductees’ fans, transforming Canton into a rollicking yet respectful RFK tailgate.

Soon after the national anthem, 2007 inductee Michael Irvin took the podium and was booed long and lustily, as if the former Dallas Cowboys wideout were still standing across the line of scrimmage from Green. According to NFL broadcaster and former coach Steve Mariucci, the crowd was “95 percent Washington Redskin jerseys!”

The fans’ journey to the cradle of professional football to pay homage to Monk and Green began less in a place than a time, when the Redskins were frequently atop the NFL, led by groups of men nicknamed the Fun Bunch and the Hogs. Among the most skilled were Green, the loquacious, lightning-quick cornerback who played longer for the Redskins than any player, and Monk, the sure-handed wide receiver who let his solid play speak for him.

Monk and Green were enshrined with former New England Patriots linebacker Andre Tippett; Gary Zimmerman, an offensive lineman for the Minnesota Vikings and Denver Broncos; Fred Dean, the pass-rushing demon of the San Diego Chargers and San Francisco 49ers; and Kansas City Chiefs cornerback Emmitt Thomas, who also mentored Green and Monk for eight seasons as a Redskins assistant.

Monk’s selection in February to Canton was the culmination of a rejection process that went on for almost a decade, as other, more showy wide receivers and less-accomplished players received enough votes for enshrinement. Monk resigned himself to being known as the durable yet often unspectacular pro, the guy who did not have enough go-long highlights to impress a suddenly pass-happy league.

Never mind Monk held the NFL’s career record for receptions for two years, had five seasons with more than 1,000 receiving yards and that he caught seven passes for 113 yards in Super Bowl XXVI. For seven years, it didn’t matter.

“I think the first year was probably the worst, because there was so much anticipation from my community, all the fans, just saying, ‘Oh, you’ve got it made, you’re a shoo-in,’ ” Monk said Friday during an interview session. “And when you start hearing that and you start believing it and when it didn’t happen, it was a disappointment.”

“It’s taken eight years,” Monk added. “But regardless of how long it’s taken, it’s good to be here.”

Green’s induction came almost as quickly as the blinding speed of the player four times named the NFL’s fastest man. He was enshrined the first year he was eligible.

Before every split time was news at an NFL combine and every team had an army of strength and speed coaches, Green once ran a 40-yard dash in an unheard-of time of 4.17 seconds.

He played 20 years with the Redskins, an NFL record for years spent with one team equaled only by former Rams offensive lineman Jackie Slater. Monk’s 295 games with Washington remains a milestone for a player with one team in one city. His seven Pro Bowl selections were buttressed by 54 career interceptions.

The fans who invaded Canton this weekend all had their favorite Green and Monk moments, ranging from Green’s spectacular punt return against the Chicago Bears in a 1988 playoff game — he winced in pain from a rib injury as he crossed the goal line — to Monk’s record-setting reception against the Denver Broncos at RFK Stadium on “Monday Night Football” in 1992, after which Monk’s teammates interrupted the game to carry him on their shoulders.

“So I guess that would be the most memorable for me,” Monk said.

A Los Angeles Rams fan, standing near Redskins fans, volunteered he had never imagined Eric Dickerson being caught from behind by any player in his prime, but that he remembered Green tracking down the tailback and dragging him to the ground.

Dan Bee, who came from Orange County, Calif., with his wife, Stephanie, said the play that sticks in his mind is Green knocking away a pass against the Minnesota Vikings on fourth down near the goal line at the end of a playoff game, sending the Redskins to Super Bowl XXII in 1988.

Keith McCoy and David Sutherland, both 24 and best friends growing up in Northern Virginia, simply remember attending Monk’s camp four straight summers, how gracious the three-time Pro Bowl wide receiver was to impressionable youths like themselves. “He signed autographs, took pictures, talked to us, everything,” McCoy said.

Monk was presented by his son, James Arthur Monk Jr. Green’s presenter was also his son, Jared, whom he and his wife were going to name Darrell Green Jr. before changing their minds a month before he was born.

“I’m so grateful because he’s his own man,” Green said. “I’m more proud of my son being my son than I am being in the Hall of Fame.”

Inside the Hall of Fame, through the maze of exhibits and grainy NFL Films, thousands more burgundy-and-gold-clad people made their way to the bronzed-bust room, where they snapped photos of Joe Gibbs’s likeness. This, too, was part of the journey to pro football’s Mecca. For this day, they wouldn’t be anywhere else.

Heady Days, Immortalized Where the Ticker Tape Fell

Stories

September 30, 2004

BLOCKS By DAVID W. DUNLAP

![]() N the midst of the longest ticker-tape drought in a quarter century, lower Broadway – the Canyon of Heroes – has been paved instead with 164 granite plaques from Bowling Green to the Woolworth Building.

N the midst of the longest ticker-tape drought in a quarter century, lower Broadway – the Canyon of Heroes – has been paved instead with 164 granite plaques from Bowling Green to the Woolworth Building.

They commemorate ticker-tape parades from October 1886, when the Statue of Liberty was dedicated, to October 2000, when the Yankees last won the World Series. They were commissioned before 9/11 under a plan by the Alliance for Downtown New York to improve the streetscape with new sidewalks, lampposts, signs and wastebaskets.

Only in recent weeks has the parade chronology been finished from beginning to end. Thirty-six intermediate plaques will be installed as permitted by construction projects along the route.

Against the shadow of Sept. 11, 2001, these plaques recall a carefree, exuberant, giddy spirit that may be difficult to conjure again downtown, even if the Yankees do their part.

Carefree? How about the parade in May 1962 when President Félix Houphouët-Boigny of the Ivory Coast was cheered as “Scott Carpenter” by spectators who mistakenly assumed he was a newly returned astronaut.

Exuberant? How about the 1,900 tons of paper showered on Douglas (Wrong Way) Corrigan in August 1938 after his flight from New York to Ireland “instead of his ‘intended’ destination of California,” as the plaque says, with quotation marks that constitute one of the few instances of editorializing.

Giddy? How about May 1950, when there was a parade every day for three days, beginning with one for Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan of Pakistan. He was assassinated a year later, one of many foreign leaders who were hailed in the Canyon of Heroes and then jailed, deposed or murdered back home.

“It was almost like a death sentence to get a ticker-tape parade,” said Kenneth R. Cobb, the director of the municipal archives, who has compiled a parade history.

After several spontaneous outbursts, one of the first organized uses of paper tape from stock-market tickers occurred Nov. 18, 1919, in a parade for the Prince of Wales, later the Duke of Windsor.

Grover A. Whalen, the city’s official greeter, recalled in his 1955 autobiography, “Mr. New York,” that he arranged a word-of-mouth campaign among downtown businesses to give the prince a spectacular reception with streams of ticker tape. It wound up including torn-up phone books. (Hmmm. A city official, proud of his Irish descent, contriving to welcome the Prince of Wales by inundating him with waste paper thrown out of windows in tall buildings.)

Watching the paper fall on the Yankees in 1996, Carl Weisbrod, the president of the Downtown Alliance, and Suzanne O’Keefe, the vice president for design, agreed that something should be done to commemorate the parades.

As part of the $20 million streetscape project, under the direction of Cooper, Robertson & Partners, the design studio Pentagram came up with the idea of simple granite sidewalk strips – not unlike the ticker-tape ribbons that remain after a parade, said Michael Bierut, a Pentagram partner – with the date and a few words of description.

(An illustrated brochure and map with information about all 200 parades can be picked up at kiosks outside City Hall and the World Trade Center PATH station or through the alliance, at downtownny.com or 212-835-2789.)

The plaques were made by Dale Travis Associates, the firm responsible for the silver-leaf lettering in the Freedom Tower cornerstone. The granite blocks, 8 inches wide and 3 inches deep, were cut with a water jet, Dale L. Travis said. Then the two-inch stainless-steel letters were inserted, held by pins and thermoplastic grout.

Last week, Jorge Condez and Paul Corrales of A.F.C. Enterprises set some of the last plaques, including “October 28, 1986 * New York Mets, World Series Champions,” into place near Vesey Street.

THREE years and 11 months have passed since the last parade, the longest interval since the 1978 Yankees broke a nine-year dry spell in the Canyon of Heroes.

The next parade will not be easy. The image of a paper blizzard suspended in midair among the downtown skyscrapers, once a visual metaphor for civic celebration, was transformed on Sept. 11, 2001, into a metaphor for cataclysm.

Is it still? Mr. Bierut hopes not. “Part of the resiliency of the city is retaining its own meaning for those metaphors and not surrendering them,” he said. “The post-terror condition has acclimated people to view any disruption of routine as a cause for alarm. There will come a time when the disruption of the routine of city life is seen as something wonderful.”

“Ticker-tape parades were the very essence of that,” Mr. Bierut said.

Just in case, Ms. O’Keefe said, there are 33 blank spots available on Broadway and Park Row to mark future parades. At the current pace, she figured, that ought to last a century and a half.

Patriots' Brady Disappointed in the Plaxico Score

Brady, New York Giants, NFL, PatriotsMan.

the Pats are LOVING this……

The New York Football Giants Land In The Valley Of The Sun

StoriesCHANDLER, Ariz. — Giants defensive end Michael Strahan arrived at the first of many Super Bowl news conferences dressed in all black. Five teammates and his coach appropriately followed suit.

Linebacker Antonio Pierce said none other than Coach Tom Coughlin put him in charge of the team attire for the Giants’ first public appearance after arriving in Arizona on Monday. Pierce told all participants to wear black suits as a sign of unity.

The fact that Coughlin allowed Pierce to make that decision fit perfectly with the Super Bowl theme of the kinder, gentler Giants coach. That sure-to-be-told story line, along with a few others, kicked off Monday, as the Giants met the national news media here for the first time at their team hotel.

“He opened up to everybody,” Pierce said of Coughlin this season. “He’s showing us his teeth. He’s letting us know he has cheekbones and everything.”

The kinder Coughlin emerged as a favorite topic Monday. Pierce and his teammates described bowling nights and casino nights introduced this season by Coughlin. They spoke of the leadership council he formed.

Pierce said players who rarely dealt with Coughlin did not know who their coach really was. That changed this season, according to the Giants.

The new Coughlin stood at the podium Monday, wearing the requisite dark suit and a red tie, hair parted just so underneath two bright lights pointing toward his head. The new Coughlin turned his opening news conference into a stand-up comedy routine, cracking a couple jokes.

Of the crowd of reporters gathered around him, along with dozens of TV cameras lining the back wall, Coughlin quipped, “This is like a normal day in New York, media-wise.”

Of the Giants’ 10 victories on the road this season, Coughlin joked, “We have a lot of secrets we can’t share with you.”

The Monday session was basically a preview of what this week will be like for the Giants. Surrounded by a small army of reporters, cameramen and radio hosts, they answered the same questions dozens of times, even in this first setting. There was no trash talk, at least not Monday.

The Patriots arrived in Arizona on Sunday night, but the Giants elected to land Monday afternoon. Most players described a subdued flight. Several Giants even slept. Others watched the movie “Michael Clayton.” The buzz picked up as the plane neared landing, with Coughlin describing the feeling of “anticipation and excitement.”

The Giants went straight to the team hotel, the Sheraton Wild Horse Pass. If they were looking for seclusion, the hotel provided it. Located outside of Phoenix, the hotel sits in the Sonoran Desert, surrounded by mountains and cactuses, instead of fans and bars. The hotel complex includes two 18-hole golf courses and a spa that measures 17,500 square feet.

The six Giants selected to participate in the news conference talked of savoring the experience of the week. Strahan and receiver Amani Toomer recalled what it felt like to lose a Super Bowl, the fireworks exploding for the team that beat them, the newspaper the next morning announcing their loss.

“If you lose,” Strahan said. “What is there to remember?”

As if playing the undefeated Patriots did not serve as enough of a challenge, the Giants also came down with a flu bug this week. Coughlin said the bug surfaced in the past day or two, and that three players missed practices with high temperatures. Coughlin said he hoped the sickness “will not be an issue.”

And with that, attention turned back to the story lines sure to dominate the week. Coughlin said the Giants were familiar with the underdog role. He repeated that he never considered not playing his full roster when the Giants faced the Patriots in the regular-season finale.

Across the ballroom, punter Jeff Feagles talked of remembering the experience. A 20-year veteran, Feagles has never been in a Super Bowl before, same as Coughlin, his kinder, gentler head coach. Feagles talked of how fast the plane ride went by, of how giddy his teammates were.

At the airport, he pulled out a camera and started taking pictures. And with that, Super Bowl week was under way for the Giants.

“This is special,” Feagles said. “I’ve been to that airport I can’t tell you how many times. But this felt different. This felt good.”